Zaha Hadid: The Suprematist Architectz

A lot of texts written in the past years put in perspective the influence of the Suprematist mouvement and its leader, Kasimir Malevitch, in the work of contemporary architect Zaha Hadid. Most of the research explains the ways in which the buildings designed by the Iraki architect can be associated to this Russian avant-garde mouvement, but it seems like this association goes way beyond a simple matter of influence. Some of the early works of Hadid tie in perfectly with the representational system of suprematism, even more perfectly than in the architectural experimentation of Malevitch himself.

Suprematism. Soccer Player in the Fourth Dimension

Kazimir Malevitch

In the text Zaha Hadid and Suprematism, Mélodie Leung presents the work of Malevitch as being characterized by four principles: abstraction, distorsion, fragmentation and the absence of gravity. Of course, those four principles are not the only ones that can be used to qualify the artworks of Malevitch, but they give a good base to resume the impression engendered by paintings like Suprematism; Soccer Player in the Fourth Dimension or Two-Dimensional Self-Portrait. In these two artworks, and in most of Malevitch’s work, abstraction is taking the place of the figurative tradition, even if there’s still some references to real life in the titles. The forms used in the composition are all placed in unique perspective and it looks like if they had suffered from distorsion and fragmentation. The monochrome background erases all the possibilities to imagine the space of the painting as being tridimensional. All the objects are in an anti-gravitational space, constituting what we could call the blank aesthetic.

Two-Dimensional Self Portrait

Kazimir Malevitch

However, this blank aesthetic isn’t really present in the architectural works of Malevitch; though they were designed to embody the continuation of the suprematist project by finding the degree zero of architecture. Like Yve-Alain Bois wrote in an article, the architectones were made to demonstrate the possibility of an abstract architecture liberated from the links with Earth and the law of universal gravitation. It seems, nonetheless, that the the aesthetic of the architectural exploration of Malevitch is really far from that and from the impression associated with the pictural work.

Unpacking and identification of architectones' elements, in Jean-Hubert Martin, "Archeology of Architectones", Les Cahiers du MNAM, January / March 1980, p. 150-151

The architectones are more likely to be associated to an extension of the international style than to the blank aesthetic proper to the suprematist movement, and that may be explained by the fact that Malevitch was in contact with Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier from 1920 until the end of his career. The choice of orthogonal and complete shapes, assembled in an additive way and the exclusive use of the square as a base for each one of the structural elements is creating a direct link with the utilitarian style of the european modernists. In the Painting the Absolute monograph, Andrei Nakov is putting in evidence the fact that Malevitch’s work:

"[...] allowed the new architect to work with an unprecedented freedom, for his building material, having become exponentially functional, was now utterly subordinated to his design, rather than vice versa".

It though seems like, even if he had that freedom, he decided to limit himself to only one shape in the composition of his architectural experimentation.

Zaha Hadid and Suprematism Exhibition

Courtesy of Galerie Gmurzynska

Even if this choice could be thought of as being logic and coherent, the square was not an appropriate choice to recreate in 3D space the same dynamic effect that was inherent in the plane artworks. The use of a fragmented vocabulary could have matched the suprematist program better; and Zaha Hadid proved it.

In addition of her contribution in the theory of the russian avant-garde, brought through the scenography of the Great Utopia: The Russian and Soviet Avant-Garde 1915-1932 in 1992 at the Guggenheim Museum of New York and the curation of an exhibition at the Gmurzynska Gallery of Zurich putting in relation her work with the artworks of Russian painters, Hadid contributed indirectly to the comprehension of the suprematist movement with her practical work. Her preparatory drawings, but also her early works realized between 1980 and 1990, before she adopted the fluid aesthetic for which she is today recognized, shaped what suprematist architecture could have been.

Hoenheim-Nord Terminus and Car Park by Zaha Hadid Architects

Painting, Courtesy of Zaha Hadid Architects

Hoenheim-Nord Terminus and Car Park by Zaha Hadid Architects

Photograph by Roland Halbe

Buildings like the Hoenheim-Nord Terminus and Car Park, for example, reminds intuitively of Malevitch’s artworks, but the resemblance is even clearer in the dynamic of projects like the Spittelau Viaducts Housing, the Vitra Fire Station and the New Campus Center.

Those buildings are perfect architectural equivalent of the suprematist’s blank aesthetic using abstraction, distorsion, fragmentation and absence of gravity as part of the conception and composition process. Forms are not assembled in an additive logic forming pyramidal structure like Malevitch’s architectones, they are rather designed in a way where shapes can be mixed and interfere one with another through interpenetration. It’s also that process that gives Hadid’s building the impression that they’re not subject to gravity since it allows unlikely organisation like the leaning roof of the Vitra Fire Station, for example, or the inverted pyramidal structure of the Spittelau Viaducts Housing Project. The same type of phenomenon is also visible in the interior design of the New Campus Center.

Spittelau Viaducts Housing by Zaha Hadid Architects

Photograph Bruno Klomfar

Vitra Fire Station by Zaha Hadid Architects

Photograph by Christian Richters

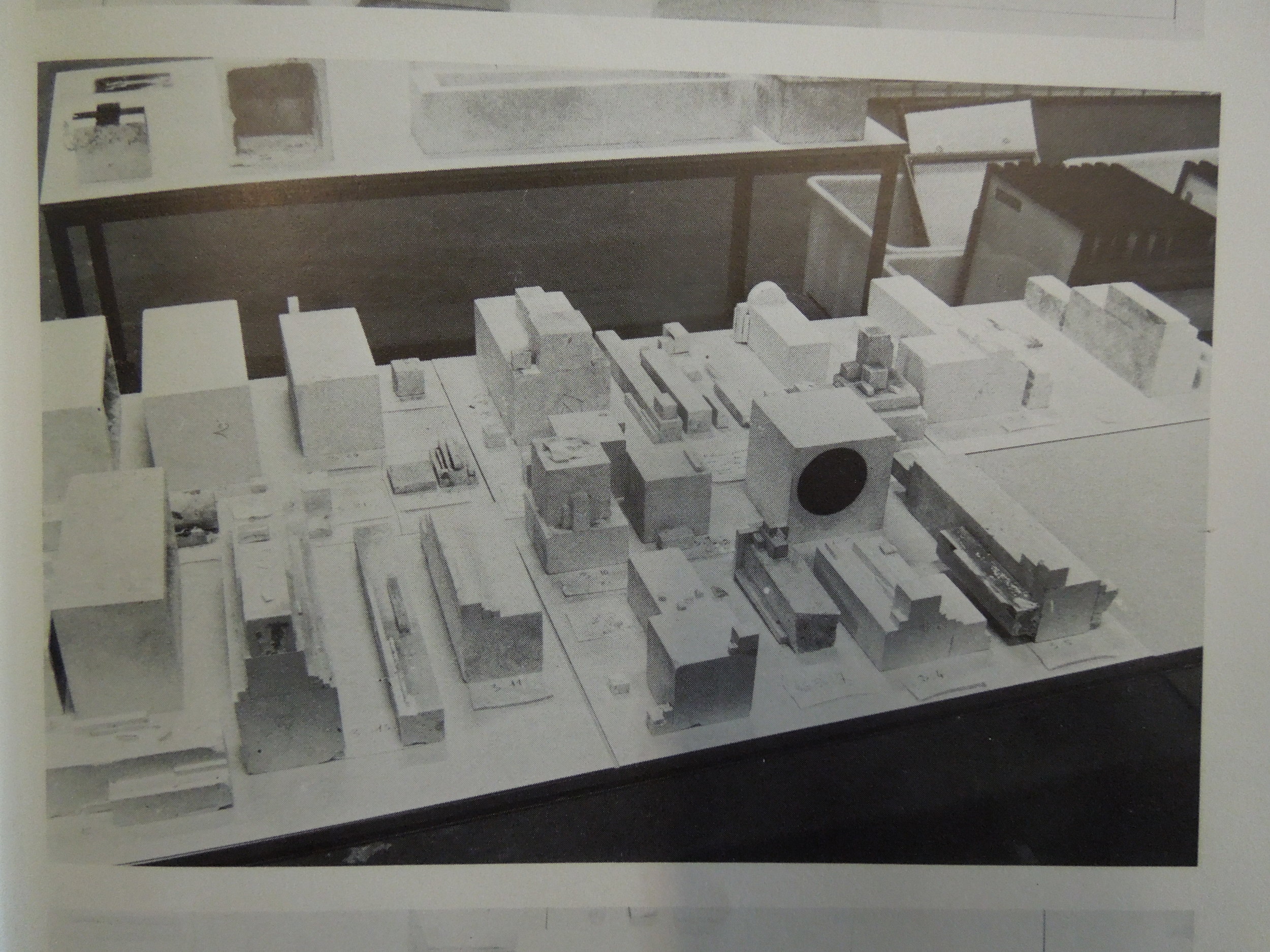

New Campus Center by Zaha Hadid Architects

Model Photography by Zaha Hadid Architects

Zaha Hadid’s work joins the principles elaborated by Kasimir Malevitch in the beginning of his career in a clearer manner than the architectural experimentation he did himself. Even if the architect was undoubtably inspired by the suprematist’s work, it would be hard to know if those characteristics are there in an intentional manner or if they are only the unconscious product of a solid knowledge of Malevitch’s program. Either way, Zaha Hadid buildings allows us to understand the Russian avant-garde movement in another way by bringing to life the idea of a degree zero architecture; created by nothing else than the human genius.

Head image by threefold