100 Years Of Bauhaus

Bauhaus is mostly associated with design and architecture — with pragmatic functionalism, geometric shapes and primary colors that would finally say goodbye to nostalgic ornaments and historical references. The catastrophic experiences of WWI motivated the Bauhauslers to rethink life, society and the everyday world radically. Rejecting traditional knowledge, the Bauhaus forged a school of design in which young people were to develop their artistic creativity. By learning with and from materials, they aimed to give shape to the modern age and meet its many demands. In doing so, the focus was less on the individual work of art than on everyday objects which were to be manufactured in collaboration with industry.

View of the magazine Bauhaus-Zeitschrift, No. 2/3, 2nd year, 1928 being placed on a flat surface, Dessau, Germany — Collection Centre Canadien d'Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal

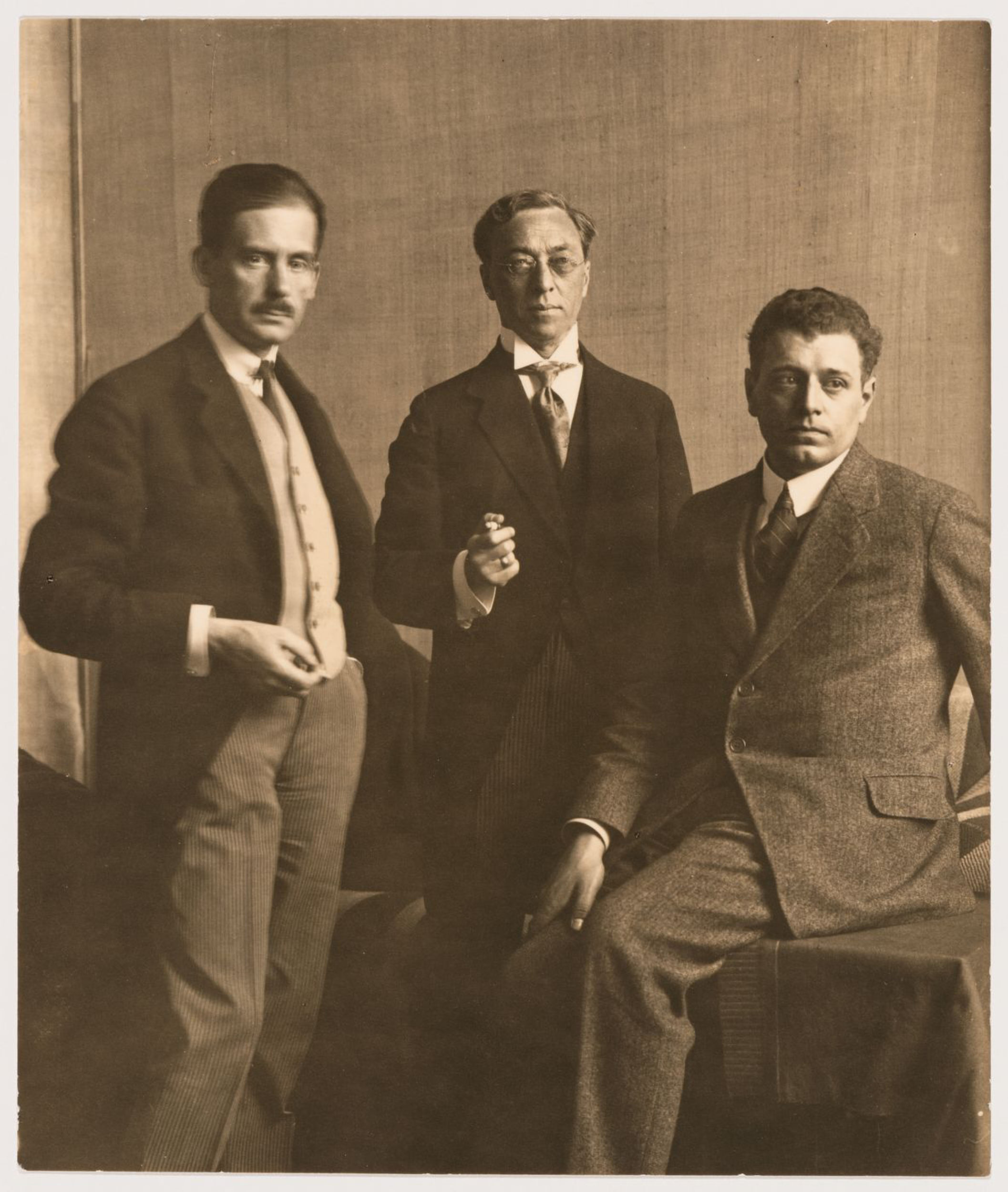

During the 14 years spell of intense, life-changing creativity, the influential design school existed in three German cities; Weimar (1919-1925), Dessau (1925-1932) and lastly in Berlin (1932-1933), and was during the period directed by Walter Gropius, Hannes Meyer, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. In 1933 the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime, having been painted as a center of communist intellectualism.

Portrait of J.J.P. Oud, Wassily Kandinsky and Walter Gropius at the Bauhaus Exhibition of 1923 in Weimar, Germany — Collection Centre Canadien d'Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal

The most significant period was when the school was located in East German Dessau from 1925 to 1932. Designed by Walter Gropius, the founder of Bauhaus, the historic building embodies the core principles and values that define the holistic epochal art- and design movement that still echoes in contemporary design today. The building’s objective was to facilitate the creation of a Gesamtkunstwerk — a total work of art — where everything was designed as a whole entity.

View of the Bauhaus by Walter Gropius, in Dessau, Germany — Collection Centre Canadien d'Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal

The bold and progressive campus features an asymmetric pinwheel plan, with dedicated areas for teaching, an auditorium and offices, and housing for students and faculty distributed throughout three wings connected by bridges. The design does not visually amplify the corners of the building, which creates an impression of transparency. Gropius designed the various sections of the building differently, separating them consistently according to function. He positioned the wings asymmetrically; the form of the complex can thus be grasped only by moving around the building. There is no central view.

Interior view of the Bauhaus building showing two chairs designed by Mies van der Rohe and a table and stool designed by Marcel Breuer, Dessau, Germany — Collection Centre Canadien d'Architecture/ Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal

The Bauhaus promoted a unified vision for the arts that made no distinction between form and function, as well as an appreciation of the evolving relationship between art and industry. “Bauhaus strives to unite all artistic disciplines — sculpture, painting, crafts and crafts — into a new building art (...) Architects, sculptors, painters, we all have to return to the craft,” Gropius wrote in the manifesto that defined the school. The manifesto attracted not only lots of students from all over the world but also artists such as Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky and Johannes Itten, who, as masters, were to shape the students creatively. Gropius wanted to create a new breed of artists, who could turn their hands to anything. Traditional art schools were conservative and elitist. Technical colleges were dreary and conventional. Gropius broke down the barrier between fine art and applied arts.

Both the school’s director and instructors lived in four semi-detacheds “Masters’ Houses” on the campus, designed by Gropius. Part artist colony, part utopian estate, these homes combined work and leisure spaces into a living, breathing manifestation of the Bauhausian dream and became the artists’ colony of the twentieth century.

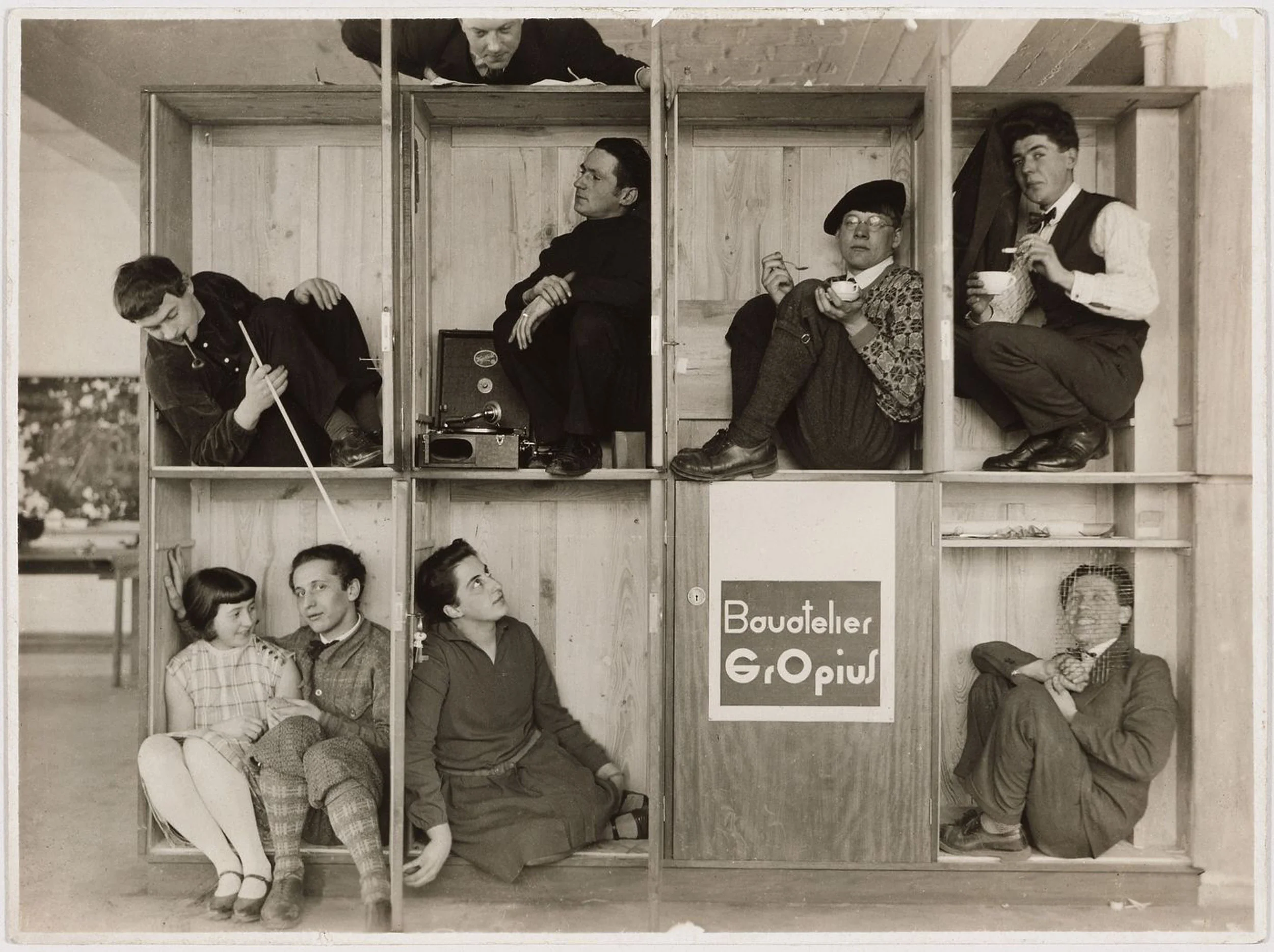

Group portrait of Walter Gropius and his students in Gropius' Bauhaus studio, Dessau, Germany — Collection Centre Canadien d'Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal — Copyright: © Ursula Kirsten-Collein, Berlin

Interior view of a studio apartment in the Bauhaus building showing a bed, round table and side chair designed by Marcel Breuer, Dessau, Germany — Collection Centre Canadien d'Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal

Students learned pottery, printmaking, book-binding and carpentry. They studied typography and advertising. They went back to basics and began again with fresh eyes. The completed building encapsulated the notion of a Gesamtkunstwerk, with interior fittings, furniture and lighting produced in the school’s workshops. Spartan interior such as Marcel Breuer’s world-famous design classics, the mid-1920s steel pipe furniture, Josef Alber’s geometric shelves-system in wood to Otto Lindig’s significant pottery, Martha Erps graphical weaving techniques, and well-designed accessories like Max Krajewski’s silver-bronze tea-glass with ebony handles becomes a unit of elegance in the building.

Interior view of the administration wing of the Bauhaus building showing a corridor, Dessau, Germany — Collection Centre Canadien d'Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal

The broad, interdisciplinary approach taken by the school’s instructors and their students considered fine arts, graphic design, advertising, architecture, product and furniture design, and theory not as separate fields, but as parts of a conversation about living in the modern world and with ambition towards the betterment of society. Though the Bauhaus set its sights on bringing its ideas into the mainstream, during the complexity of the interwar years, these concepts were still considered avant-garde.

Bauhaus-style architecture, Wroclaw, Poland — Collection Centre Canadien d'Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal

Despite the closure of the school in 1933, the ideas of the Bauhaus spread worldwide. Many of the Bauhaus masters went into exile and became professors at successor institutions. The students who arrived at the Bauhaus Dessau from 29 different countries also disseminated the Bauhaus ideas in their homelands.

Bauhaus cannot be reduced to one single concept. The school changed artistic directions several times. Bauhaus was a school, a workshop, an idea — but never a style. The historic Bauhaus moved between the realms of radical utopia, social vision and reality. Its goal was to develop timely designs for everyday life. These ideas were most consistently and most emblematically actualised and inscribed into the fabric of everyday life with the Bauhaus buildings in Dessau. The Bauhaus astonished and, in some cases, horrified contemporaries.

Axonometric drawing and section for a student project at the Bauhaus — Collection Centre Canadien d'Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal

It was a new way of thinking, and at the end of WWI, a new century was born. Its ideas still set the pattern for the way we live today. Mies van der Rohe’s famous motto, “Less is More”, or the iconic manifestation of Louis Sullivan's “Form follows function” are clear examples of how Bauhaus principles are still highly relevant. Today Bauhaus influences can be seen everywhere from furniture to graphic design. An instigator in the minimalism trend which is still one of the most popular styles to date, Bauhaus helped the design world step away from the ornate designs of the early 20th century with its emphasis on function rather than form. Other leading styles, like Scandinavian, industrial and mid-century modern, are unmistakable in their Bauhaus influences, showing how far the spread of the school’s teachings have reached.

Once a radical revolt against the status quo, the Bauhaus style has become the new normal. And by becoming ubiquitous, it has disappeared - into the décor of our daily lives.