Q+A with Designer Aela Vogel, Questioning Gender with Theoretical Sex Toys

Aela Vogel is a Zurich-based designer. Her master’s thesis project, Genderfull, consists of a series of sex toys aiming to spark critical debate about gender. Relevant and intriguing, her work captured our team’s attention, leading me to dig deeper by asking Vogel a few questions…

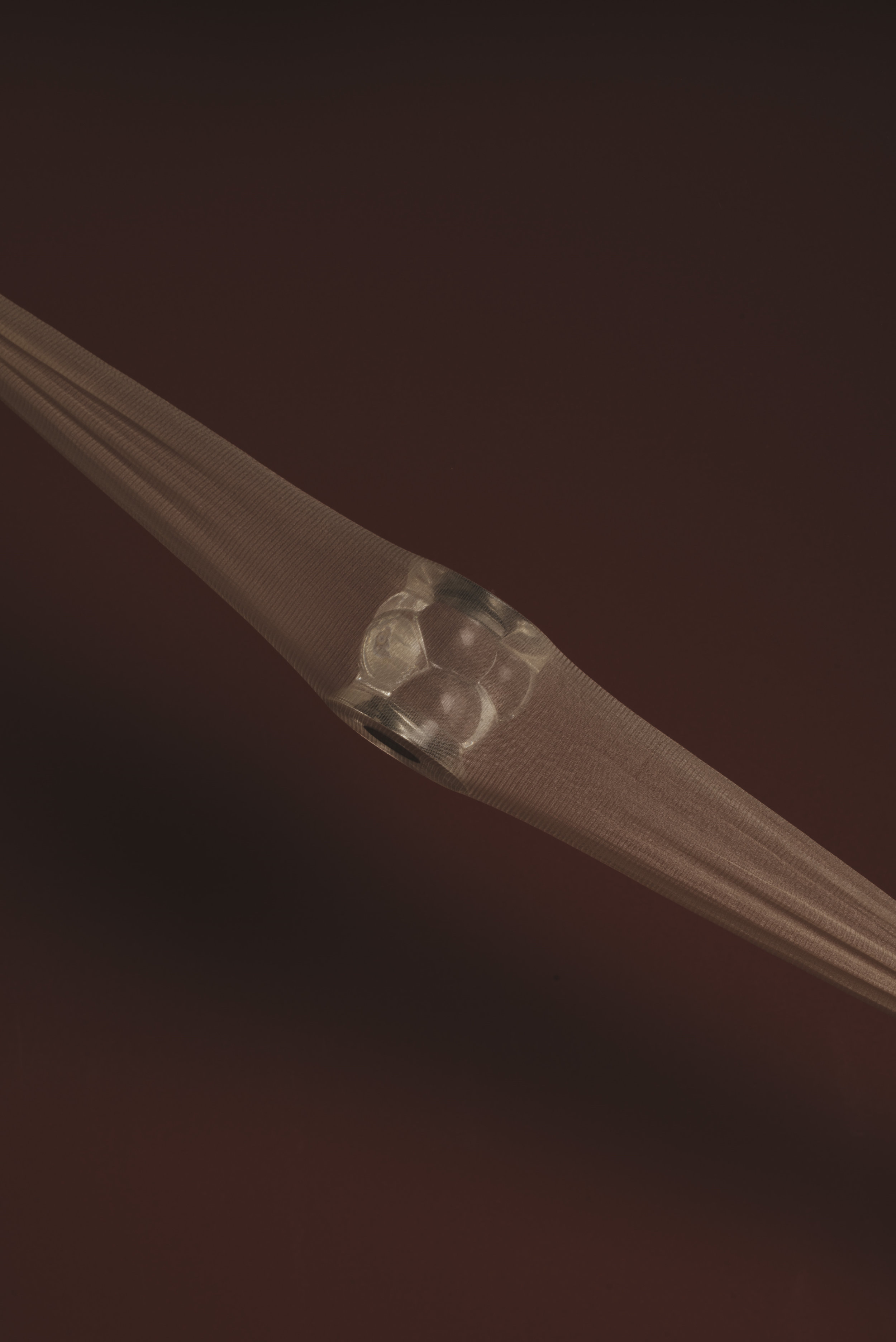

All images by Corinna Hopmann

EL : I guess the questions that are sparked regarding the utilization of your theoretical sex toys are on purpose. But could you explain to us how your objects are supposed to work? Or why do you intend to make their utilisation ambiguous?

AV: As a design researcher, I am fascinated by theoretical and intangible knowledge, like the socio-cultural phenomena of gender. As a product designer, I am intrigued by design’s ability to translate these socio-cultural phenomena into physical and tangible representations. My work provides others with classic aesthetic depictions of unclassified design, namely genderless design, and offers a showcased opportunity to understand its fundamental components.

I aimed to create a playing field that opened the debate for others to talk about gender in an inclusive manner. I conducted a series of scientific and ethnographic experiments to understand the core differences between people’s perceptions of aesthetics in design. What makes something masculine, what makes something feminine and where do we draw the line; when do things become so unclear that we define them as neither; genderless?

My work aimed to explore whether formal design aesthetics in products can be identified and carefully reconstructed to consciously cater to the broadest possible spectrum of needs. To provide the playing ground I needed to transfer the theoretical knowledge to design in an attempt to transmit knowledge to users with the potential to spark critical debate.

The reason its utilization is intended to be ambiguous is because I wanted to design something entirely inclusive and open to interpretation. There is no single answer as to what is considered feminine, or masculine. This is defined by the user and their perception or understanding. What I provide is a conversation starter into the topic of gender and its spectrum.

EL : Some could argue that it is rather paradoxical to use sex toys to talk about gender —since theories seem to inherently distinguish these two things. Why did you decide to go in that direction?

AV : I agree that it could seem paradoxical to use sex toys to talk about gender – however, it is precisely this assumption that I play with. Design and sex are both informed by emotional, socio-cultural and visual factors, allowing for the hypothesis that when combined, all of these factors become naturally enjoyable and understood.

Sex and design are traditionally seen to be inclusive, one would assume that sex toys would be viewed similarly; however, it is quite the opposite. Traditional sex toys appear to be extremely exclusive to non-binary stereotypes and the broad spectrum of gender that exists, both on a personal and product level. Resembling heteronormative products, and extreme gendered aesthetics, one could argue that current sex toys go as far as dictating what we should and shouldn’t do with our bodies, and with whom we should or shouldn’t do it. They have the potential to serve as highly responsive products to explore genderless design in the form of theoretical objects.

To reach a broad audience and provoke reactions to discuss the topic of gender, not only in design but also as a social construct as a whole, the theoretical objects must spark curiosity. Simply put, the sex toy as a medium to exemplify and discuss genderless design is more provocative, more interesting and will attract more curiosity than a series of genderless handbags or watches could have.

“Resembling heteronormative products, and extreme gendered aesthetics, one could argue that current sex toys go as far as dictating what we should and shouldn’t do with our bodies, and with whom we should or shouldn’t do it.”

— Aela Vogel

EL : The idea of adaptable objects — objects that can exist in many forms and evolve — underline this idea of fluidity. Do you think that design, in its essence, should go toward this idea of not being finite? What could it change?

AV : Throughout history, design has continuously strived to reflect changes in society and catered to the needs and wants of many. Examples are manifold. Due to the fast processes of the fashion and beauty industry, they have become the first sectors to embrace the topic of genderless design, defined as design that does not lean on any gender.

Attitudes towards ideas previously considered challenging and alternative are changing. Instead of looking at this topic as a trend that is being translated in other industries, designers should tap into a mindset and acknowledge and respond to a cultural shift that is happening now. Perception of gender and its role in our personal identities has changed and will continue to do so in the future. We want to define our own gender identity free from pre-existing gender stereotypes. Therefore, I believe, that if designers want to continue to play a dynamic and constructive role in society, design has to reflect these changes and become more fluid and nuanced in its interpretation of gender.

A relevant question for the field of design is: can it help us to express more subtle, more nuanced and more fluid gender identities with the sophistication that people increasingly desire? Designers must use this notion of imbuing design with knowledge in order to create awareness about wider social topics. Arguably, product language in design has not been flexible, or quick enough to cater to the needs or wants of non-binary individuals. It is my firm belief that design should become (more) fluid and nuanced in terms of the interpretation of gender.

“I believe, that if designers want to continue to play a dynamic and constructive role in society, design has to reflect these changes and become more fluid and nuanced in its interpretation of gender.”

— Aela Vogel

EL : There seems to be an absence of duality in your design that is reflected in your title “Genderfull.” How did you end up conceiving that this term was more appropriate than “Genderless” for your project?

AV: To me, it is quite simple. I am exploring whether formal design aesthetics in products can be identified and carefully reconstructed to consciously cater to the broadest possible spectrum of needs. Rather than being genderless – objects become genderfull; a positive reform embracing the importance of gender fluidity. The term, rather than seeming to be missing something, is full of everything, suggesting a term that describes a state of being diverse, nuanced and fluid.

EL : A recurring phrase accompanying your work is “How can design spark critical debate about gender?” Do you think that bringing academic theory and politics into everyday objects can have an impact on society? How?

AV: It is critical that the topic of gender is discussed, not just in the context of design – but as a topic as a whole. The world we live in today is extraordinarily complex, our social relations, our politics, desires, hopes and fears all differ from those at the beginning of the 20th century. Despite these large differences, many key ideas informing mainstream design stem from the 20th century. In a way, society has developed and changed, however design has not adapted.

I believe strongly that if designers bring academic theory or politics into everyday objects, they can have an impact on society and the way we use, consume, and look at things. By infusing design with real knowledge, the objects can challenge narrow assumptions, preconceptions and givens about the role society has on our behaviors, our beliefs, our lifestyles – everything really. In a way, if done correctly, design can reinforce and question the status quo. Design as a whole has the capacity to raise awareness, expose assumptions, provoke action, spark debate, and even entertain in an intellectual sort of way, if done correctly.